By Mark McConville

THE INCREDIBLE life of the Russian Countess who had to escape the Soviet Union by volunteering as a nurse on the frontline of World War One has been revealed in a new book.

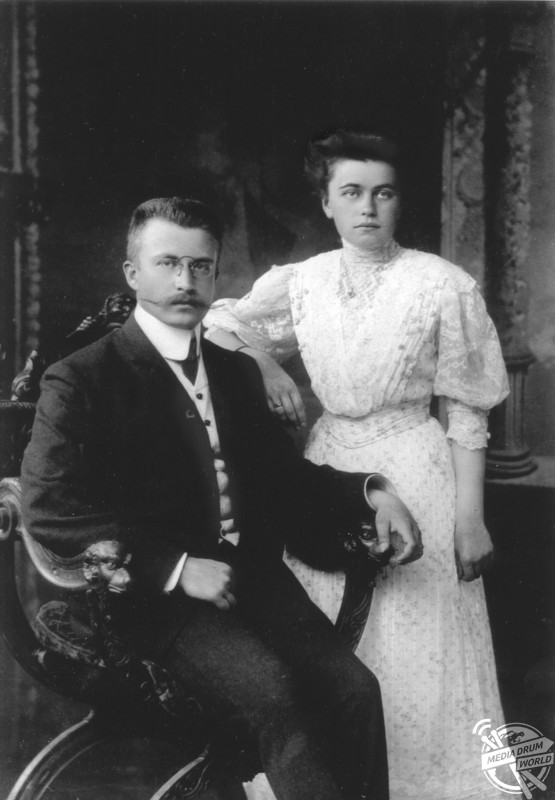

Separated from her three young sons, stripped of her possessions and fearing for her life, Countess Edith Sollohub found herself trapped in revolutionary Russia.

The daughter of a high-ranking diplomat, Edith was destined to join the social and intellectual elite of Imperial Russia. This privileged upbringing would ultimately help her survive the traumatic events of the 1917 revolution.

She assumed new identities as a Polish refugee, a travelling musician and even a Red Army nurse. She would endure hunger, imprisonment and loneliness in the quest to escape Russia and be reunited with her family.

Her thrilling tale of danger, war and escape is told in the book, The Russian Countess, by Edith Sollohub and published by Impress Books. The book has been translated into English for a new release.

The foreword in the new edition is written by Robert Chandler, who studied Russian at Winchester College under Edith’s son, Nicolas.

“Edith Sollohub was intelligent, perceptive and endowed with the gift of trust,” he wrote in the book’s foreword.

“She trusted her intuition, and her intuition did not let her down. Time and again during her two years in Soviet Russia, in situations where the wrong choice would have meant death, she trusted the right person.

“Edith Sollohub finally escaped from Soviet Russia by enrolling as a Red Army nurse during the Polish-Soviet war of 1919–21.

“Most remarkable of all, however, is Edith’s account of how she managed to cross the front line. Edith crossed the front line by not crossing it. Instead, she allowed it to cross her.

“At a time when the Poles are advancing and her unit has been ordered to retreat, she packs up her medical equipment in good time, asks for permission to go and say goodbye to her landlady and then hides in an out-of-the-way hut she has earmarked for precisely this purpose.

“Thirty-six hours later, when the fighting appears to have died down, Edith emerges into what is by then Polish territory. Soon afterwards she manages to re-join her sons.”

Edith’s escape had not come easy and was the culminations of years of hard work to escape Russia.

Mr Chandler likens her escape, achieved by staying put, to a parable and thinks there is much that can be learnt from it.

Before Edith’s remarkable getaway she had come close to death, in the winter of 1919-20 when she attempted suicide.

Her sons were safe in Estonia by then but she was still trapped in Moscow and unable to obtain a permit to leave the country, she decides to walk out into the midwinter forest until she dies of exposure. Mr Chandler took up the story.

“Unexpectedly, she meets a German (probably a former prisoner-of-war) coming towards her,” he said.

“He asks where he can find food and shelter. ‘He had fled the forests in search of a warm fire, and a piece of bread. He wanted to live – why? He had the courage to want to live, even here where everything was strange to him, where he was not wanted [. . .] “Come, I’ll show you the way,” I replied, and we walked up the long-deserted street, back into the heart of the town. I did lead him to shelter – and did he not lead me back to life?’

“This real-life parable is remarkable in many ways. For all her despair, Edith is guided by love; she chooses this particular way of committing suicide because of her love for the Russian forest.

“Setting off to die in a place she loves, she encounters the man who will save her. Most remarkable of all, she allows herself to learn from this strange figure – himself perhaps close to death – who makes what must have seemed exasperating demands and so frustrates her plans. Edith never again attempted suicide.”

The Russian Countess: Escaping Revolutionary Russia, by Edith Solohub and published by Impress Books, is out on August 1st 2017. It is available to pre-order now for £19.99.